From this article at Wikipedia:

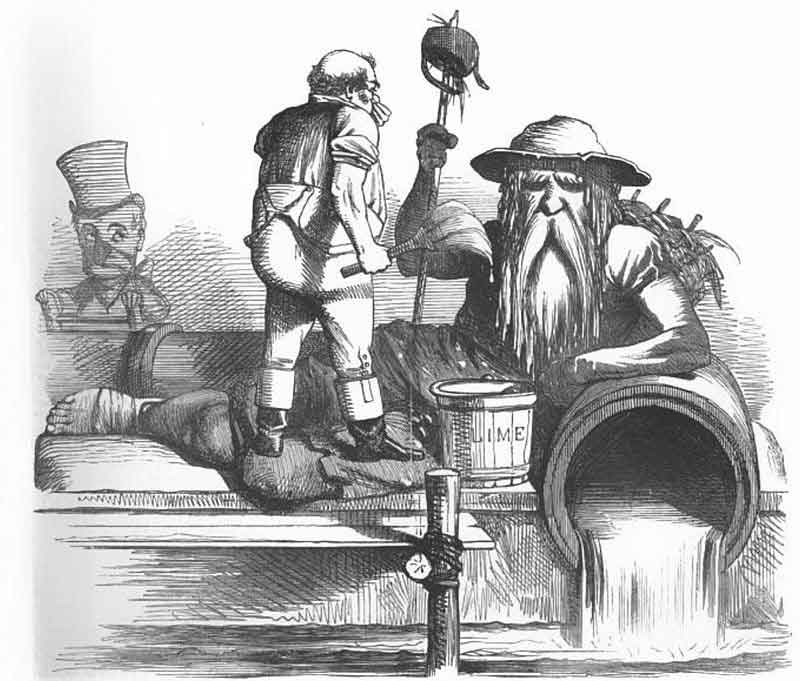

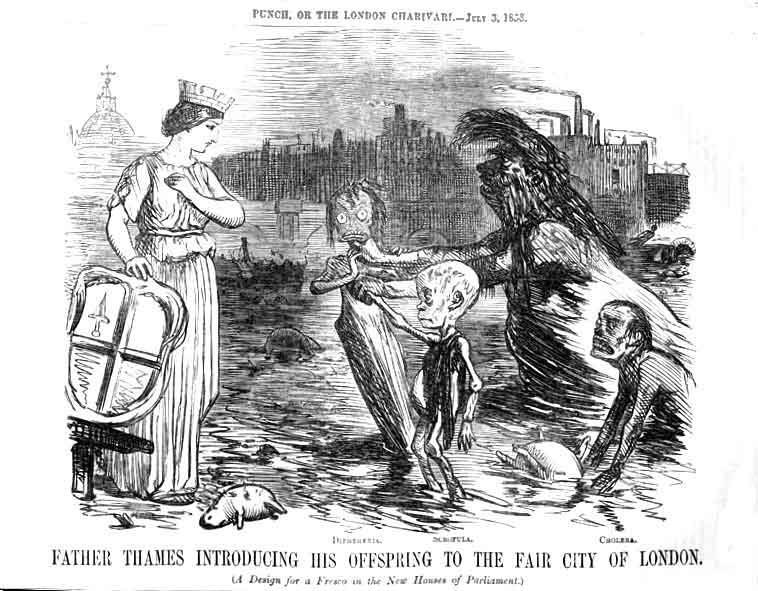

"The Great Stink" was an event in central London in July and August 1858 during which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and industrial effluent that was present on the banks of the River Thames. The problem had been mounting for some years, with an ageing and inadequate sewer system that emptied directly into the Thames. The miasma from the effluent was thought to transmit contagious diseases, and three outbreaks of cholera prior to the Great Stink were blamed on the ongoing problems with the river.

The smell, and people's fears of its possible effects, prompted action from the local and national administrators who had been considering possible solutions for the problem.

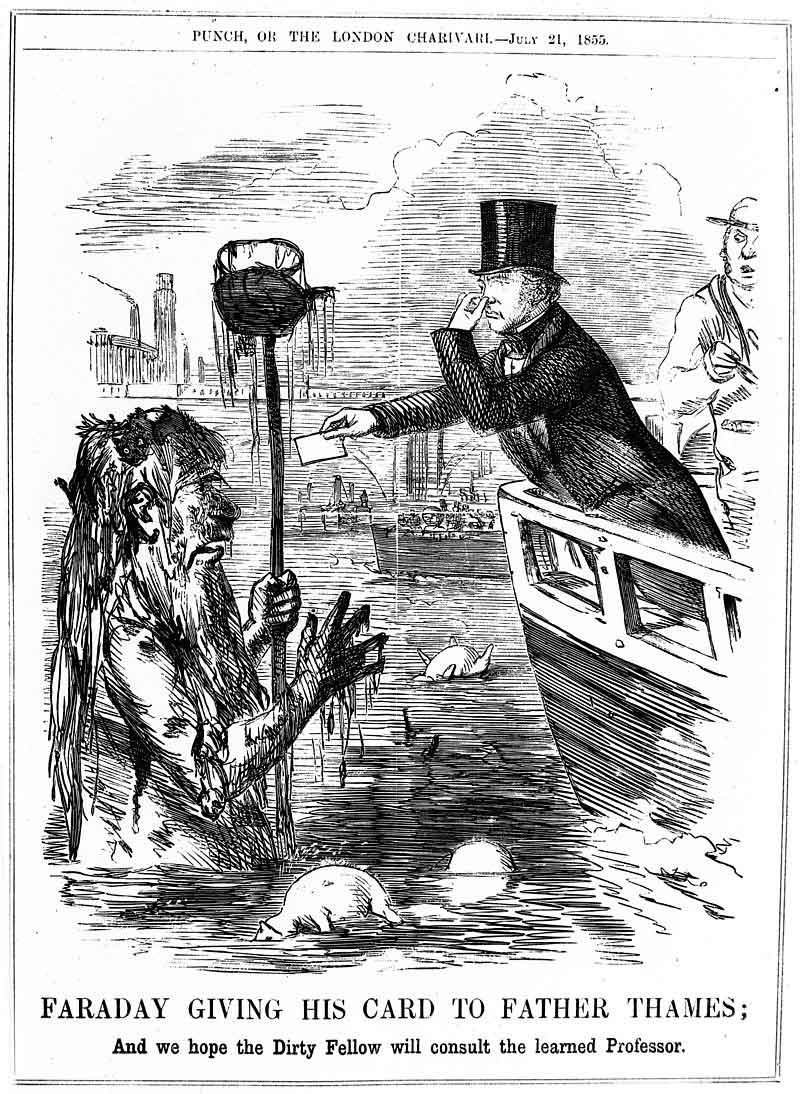

The article is wonderfully documented, a lot interesting to read and with an assortment of images that pretty much describe how people felt during the episode. Here some of them:

"Michael Faraday giving his card to Father Thames", commenting on Faraday gauging the river's "degree of opacity"

By mid-1858 the problems with the Thames had been building for several years. In his novel Little Dorrit—published as a serial between 1855 and 1857—Charles Dickens wrote that the Thames was "a deadly sewer ... in the place of a fine, fresh river". In a letter to a friend, Dickens said: "I can certify that the offensive smells, even in that short whiff, have been of a most head-and-stomach-distending nature", while the social scientist and journalist George Godwin wrote that "in parts the deposit is more than six feet deep" on the Thames foreshore, and that "the whole of this is thickly impregnated with impure matter". In June 1858 the temperatures in the shade in London averaged 34–36 °C (93–97 °F)—rising to 48 °C (118 °F) in the sun. Combined with an extended spell of dry weather, the level of the Thames dropped and raw effluent from the sewers remained on the banks of the river. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert attempted to take a pleasure cruise on the Thames, but returned to shore within a few minutes because the smell was so terrible. The press soon began calling the event "The Great Stink"; the leading article in the City Press observed that "Gentility of speech is at an end—it stinks, and whoso once inhales the stink can never forget it and can count himself lucky if he lives to remember it". A writer for The Standard concurred with the opinion. One of its reporters described the river as a "pestiferous and typhus breeding abomination", while a second wrote that "the amount of poisonous gases which is thrown off is proportionate to the increase of the sewage which is passed into the stream". The leading article in The Illustrated London News commented that:

We can colonise the remotest ends of the earth; we can conquer India; we can pay the interest of the most enormous debt ever contracted; we can spread our name, and our fame, and our fructifying wealth to every part of the world; but we cannot clean the River Thames.

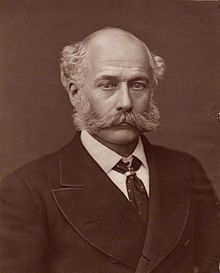

Joseph BazalgetteThe hero on this story is Joseph Bazalgette. London authorities accepted his proposal to move the effluent eastwards along a series of interconnecting sewers that sloped towards outfalls beyond the metropolitan area. Work on high-, mid- and low-level systems for the new Northern and Southern Outfall Sewers started at the beginning of 1859 and lasted until 1875. To aid the drainage, pumping stations were placed to lift the sewage from lower levels into higher pipes. His provision, associated with a drop in cholera cases, led the historian John Doxat to state that Bazalgette "probably did more good, and saved more lives, than any single Victorian official".

Bazalgette continued to work at the Metropolitan Board of Works until 1889, during which time he replaced three of London's bridges: Putney in 1886, Hammersmith in 1887 and Battersea in 1890. He was appointed president of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) in 1884, and in 1901 a monument commemorating his life was opened on the Victoria Embankment. When he died in March 1891, his obituarist in The Illustrated London News wrote that Bazalgette's "two great titles to fame are that he beautified London and drained it", while Sir John Coode, the president of ICE at the time, said that Bazalgette's work "will ever remain as monuments to his skill and professional ability". The obituarist for The Times opined that "when the New Zealander comes to London a thousand years hence ... the magnificent solidity and the faultless symmetry of the great granite blocks which form the wall of the Thames-embankment will still remain." He continued, "the great sewer that runs beneath Londoners ... has added some 20 years to their chance of life". The historian Peter Ackroyd, in his history of subterranean London, considers that "with John Nash and Christopher Wren, Bazalgette enters the pantheon of London heroes" because of his work, particularly the building of the Victoria and Albert Embankments.

Source: Wikipedia.